Why Ruins Resonate Now:

The Pleasures and Presences of the Past

Figure 1. Detail, Tomb of Nero, from the Grotteschi, Giovanni Battista Piranesi etching, ca. 1750. Overgrown, serpent-infested ruins of ancient Rome.

In the late 17th century, wealthy travelers, often English, began undertaking visits to the intellectual capitals of Europe, not for commercial or religious, or military purposes, but to further their cultural education. These aristocratic travelers, usually young men, freed of their home countries’ social constraints, sought other satisfactions as well; and period accounts are seasoned with tales of spectacular gambling debts and duels; dangerous liaisons and venereal diseases; egregious villainies and very considerable ruckus raising.

What became known as the Grand Tour might occupy a year and more, following what became a well-trod route – to Paris, Berlin, perhaps Vienna; to Florence, Pisa, Venice, maybe Naples; and always, inevitably, to Rome. Over time, this group of travelers became more democratic, including not just the scions of the wealthy and influential, but young women, the upper middle class, more Europeans, even Americans. By the 1840’s, with the opening of rail lines to Italy, tourism had become an industry. And yet with all these changes, Rome remained the destination.

Why Rome? With its twenty-five hundred year history of continuous and especially artistic innovation, from its ancient civilization, through glories Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque; on to more modern accomplishments in the Arts and Sciences in the 18th century – the city had long been the center of the world. All roads led not to Paris or London, St. Petersburg or Constantinople or New York, but to Rome. And yet, many tourists came less for what Rome had become, more for what it had been and, crucially, what had befallen the place in the interim. The allure of Rome, embedded in almost every tourist’s trinket of the period, was its ruin – the evocative, desolate, remains of a once great civilization; vast, unprecedented empire brought low fifteen centuries earlier (fig. 1).

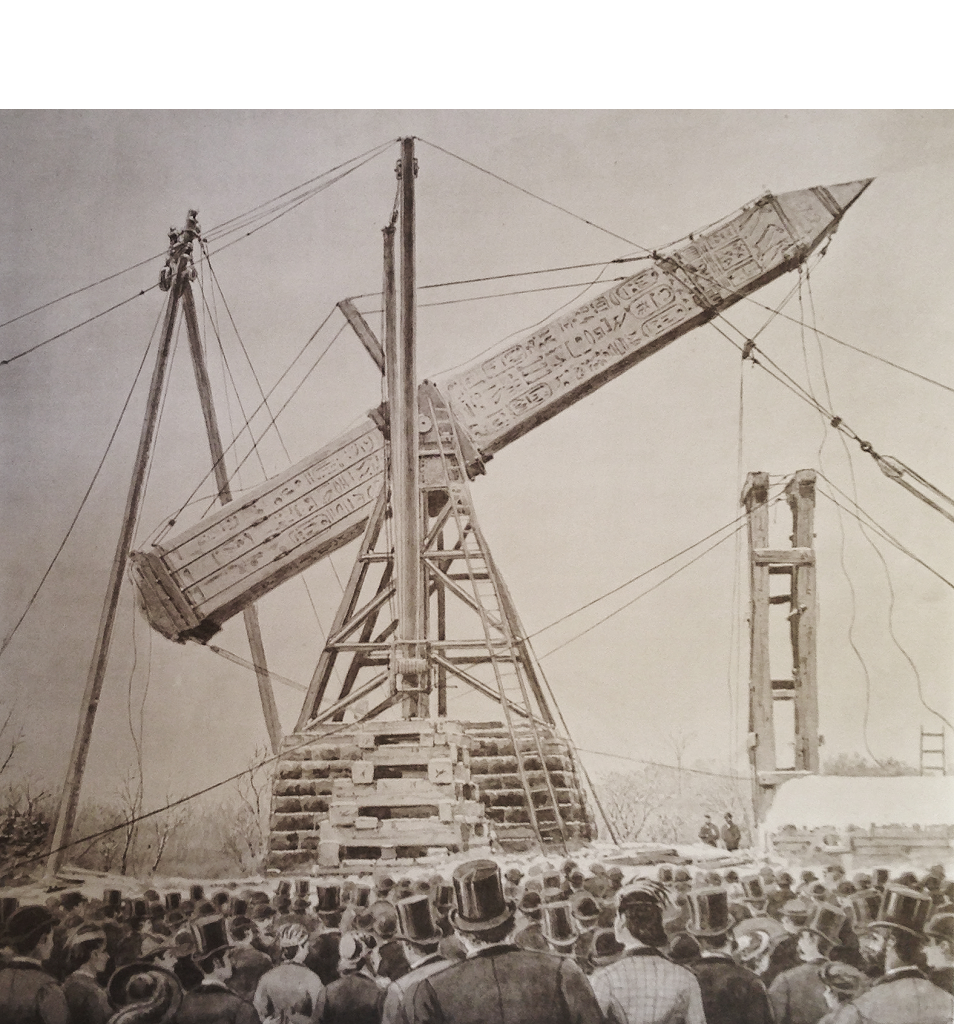

Figure 2. Detail, Turning the Obelisk, from Egyptian Obelisks, by Gorringe, Artotype, 1883. Placing the “Cleopatra’s Needle” in New York’s Central Park.

17th, 18th, and 19th century British visitors’ fascination with the place is understandable. In this period, England’s reach grew worldwide, the sun never setting on the small island’s global empire; long before, of course, the sun reliably rose and set only over London. For these English, ruined Rome may have seemed, as Berra put it, like déjà vu all over again.

The experience now of the Eternal City is similar for visitors from the United States, the American Century rapidly receding in History’s rear view mirror; its empire, our empire, by every measure, contracting.

The example offered by Rome, rather the idea of Rome at its zenith, was compelling to those fashioning later Empires, especially the British and the French in the 18th century, and Americans in the late 19th and 20th centuries. Buildings and monuments in these countries were styled Roman, as were many of the Arts. As Rome had done in the time of the Caesars, all three nations brought home Egyptian obelisks lifted from ancient archaeological sites. (There are more ancient Egyptian obelisks in Rome than in Egypt).

In New York’s Central Park, behind the Metropolitan Museum, rises the so-called Cleopatra’s Needle – an ancient Egyptian obelisk, fashioned of red granite from Aswan, first erected at the order of Thutmose III in Heliopolis, thirty-five hundred years ago. Fifteen centuries later, in 12 A.D., Egyptian dominion vanquished, and Rome’s ascendant, Augustus Caesar directed the obelisk to be floated down the Nile, and re-erected in Alexandria. In 1880, financed by a new species of potentate, tycoon William Vanderbilt (son of Commodore), the obelisk was trundled aboard a ship sailing for Gotham, the most recent of the monument’s several homes (fig. 2). What will be the next stopping off point for Thutmose’s itinerant obelisk? Tiananmen perhaps? And, with sufficient time, what place next?

Figure 3. Beneath ‘The Dome’, ‘The Crypt’ below – Sir John Soane’s Museum, London. Inset – marble pilaster capital from the Pantheon, Rome.

The great, ancient Egyptian obelisks now populating the Thames Embankment, Place de la Concorde, and New York’s Central Park, aside from embodying now dimmed and discarded aspirations to empire, are no more (and no less!) than souvenirs, albeit at a large scale.

For most of us, of course, souvenirs must be more modest, though their purposes are similar. A sojourn among Rome’s ruins today inspires (insists on, really) responses nearly identical to those three hundred years ago. We (and they) are (were) called to observe the present, while speculating on our (their) past and, inevitably, future. Souvenirs cause us to recall, re-focus, re-order our solemn reveries, as well as passages less weighty – including gelati and cappuccini enjoyed nearby Bernini’s splashing, sparkling Fontana dei Quattro Fontane in Piazza Navona, on a pleasant Roman Fall afternoon.

More cerebral delectations are taken up in “The Pleasure of Ruins,” essayist Rose Macaulay’s 1953 appreciation of tumbled down antiquity – the “stupendous past” she called it – which casts, in modern terms, the central romantic appeals of the ancient world. On the other hand, The Necessity for Ruins written a quarter century later, by American cultural geographer J. B. Jackson, is all skepticism over the craze for preserving the architectural vestiges of the United States’ “very much more recent and insubstantial past.”

Pleasure and necessity, then – an apparently opposed pair of words nonetheless capturing much of the attraction of the past and its presence; describing, as well, collectors’ interests in the architectural pictures, models, and artifacts offered by Piraneseum.

Figure 4. Architectural fragments and casts, Sir John Soane’s Museum, London.

How do we describe the passions stirred by these things; write in reasonable ways about those unreasonable, unruly, evanescent urges and interests which reliably guide us to places unforeseen or barely expected, yet wholly compelling? What is it about these old objects that is, for all of us, now so very fascinating? We undertake the following words knowing that not everyone will or can fully understand.

A more than usually interesting interview with a dealer trading in fancy, 19th century artifacts of Neoclassicism, asked after temperaments of his shop’s customers. Nearly all of these, the dealer judged, are collectors. Of these, he guessed a third to be fully in the grips of their respective passions; reason overtaken, to various extents, by heedless fascination. This group, this devoted third of collectors, will understand what follows here. We hope, of course, to engage some others – those whose enthusiasms are, for the time being, better managed.

Among our favorite places in the world is the house of an extraordinary, eccentric, Neoclassical architect who, upon marrying well, felt freed to follow his compelling fascinations with Architecture’s glorious possibilities, especially those of its Classical past and Romantic present. A description of this place is beyond our scope here, beyond that of anything yet written, so we’ll simply say something of one small piece of it (fig. 3). Alongside ‘The Corridor’, beneath ‘The Dome’, not far from ‘The Crypt’, in a ca. 1800 London townhouse belonging to architect John Soane (1753 – 1837), fixed to a tall plaster wall and glancingly washed in a nearly eerie, colored, refracted, reflected daylight – an effect named by Soane ‘la lumiere mysterieuse’ – is a small, 2000 year old carved marble pilaster capital, pried loose, not so long ago, from the interior of Rome’s ancient Pantheon.

Figure 5. 18th century architectural capricci by Leonardo Coccorante and 19th century marble models of Roman ruins at Piraneseum.

Just how this trifling memento, and several others similar, found its way from that hoary temple to the architect’s ‘Museum’ is a slight scandal; and it’s easier on our erratically delicate 21st century sensibilities to remain ignorant of the full particulars.

In London, this ornament joined hundreds, thousands of other bits, pieces, pictures, and models of various high points of the ancient architectural world, ostensibly assembled by Soane for didactic, edifying purposes – to exhibit and exemplify the various apogees of Architecture’s history, especially its classicizing past.

And yet, we imagine Soane’s satisfactions with his very singular collection ran a great deal deeper than this. Who, seeing that carefully installed, labeled, and illuminated fragment of the Pantheon, does not recall and imagine the multiple pleasures of the great building it once decorated? – the history of the place, its overwhelming, Roman scale; that dusty column of light, reaching through the huge oculus in the vaulted ceiling, sweeping across the patterned, polychrome marble floor; the dark, still, cool comforting refuge of its ancient interior on a scorching Roman Summer afternoon.

The arcane, academic word synecdoche describes the phenomenon of a part summoning forth its whole; and this is something of what’s at work in Soane’s Museum. In addition to that little piece of Pantheon, walls (and ceilings!) teem with fragments, models, and images of Rome’s Temples of Mars, Vespasian, Castor & Pollux, Neptune, and Vesta; Villa Albani and Arch of Constantine; Tomb of Caecilia Matella and Hadrian’s Villa; as well as Herculaneum and Pompeii; and Temples at Paestum and Delphi (fig. 4).

Figure 6. 19th century marble models of a ruined Roman temple and triumphal columns. An 18th century Neapolitan capriccio beyond.

Interspersed among these are objects representing London’s Palace of Westminster; Soane-designed Bank of England (rendered, on one canvas, as a ruin!); Soane-designed family tomb; the architect’s heroes (architects Inigo Jones, George Dance, Brothers Adam) and influences (Napoleon!, Hogarth, Shakespeare); and a monument to Soane’s favorite, though departed, dog – Fanny; and, of course, very, very, very much more.

The effects of this superabundance of architectural suggestion? The enormous chorus of parts rendering palpable such a vast constellation of places; a London townhouse putting us in mind of the whole of Architecture’s history? For us, the house is mesmerizing, barely comprehensible, entirely memorable. In the course of its two hundred year long residence in Soane’s Museum, the meanings of that Pantheon pilaster capital have shifted, widened; become a synecdoche not only for that great, Roman monument of the Antique, but for a very idiosyncratic London architect, his remarkable townhouse (and much-beloved dog).

Sir John Soane’s Museum is undoubtedly an interesting place. The stores are highly valuable, and the whole collection is one that the nation should prize, and the public visit again and again. But the Museum is, at the same time, one of the queerest places in the world. The building contains two or three rooms of fair size, but beyond this it is made up all of nooks, and crannies, and recesses, and lobbies, and ante-chambers, all of them filled to overflowing with the articles which the founder – an eminent architect, who died in 1837 – had collected together during many years, and with immense labour and outlay.

The Boy’s Yearly Book, 1867

Sir John, of course, would be unmoved by this skepticism, as would any passionate collector.

What, though, does any of this have to do with Italian architectural paintings, drawings, and etchings, as well as 19th century, also often enough Italian, souvenir architectural models – the types of objects offered by Piraneseum? Like Soane’s fragments, replicas, pictures, and mementos, Piraneseum’s paintings and models put us in mind of, connect us with, much that is magnificent and glorious in Architecture – its staggeringly long and inventive history; the magnificent, felicitous places people have fashioned across millenia; the sheer, overwhelming extent of the imagination and effort attached to the most memorable monuments and buildings; the architectural past and its presence (fig. 5).

These paintings and models, much more fleeting and ephemeral than Soane’s marble fragments, also work our imaginations as synecdoches – parts calling forth their wholes – fleeting images of places – colored light reflected from old paint daubed artfully across stretched canvas; the tiniest, most impressionistic tourist’s baubles – recalling Architecture’s great richness.

Yet, it is not just the alchemies of those slight pictures and models remembering the most substantial places; but the places themselves, which are at the heart of these objects’ transporting effects.

We realized only recently what must have been apparent to others for a very long time – the subject matter of almost all of Piraneseum’s pictures and models is shared, nearly identical – Italian architectural ruins and, less often, intact ancient places on that sunny peninsula (fig. 6), and throughout Europe. Paintings picture the remains of Rome’s Colosseum; Temples of Vespasian, and Castor and Pollux; Pyramid of Caius Cestius; Arch of Constantine; as well as ruins fancifully imagined, arranged strictly for pictorial, dramatic, Romantic purposes. Bronze and marble models depict the Columns of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius; a variety of Egyptian obelisks transplanted to Europe; and several medieval French cathedrals, turned out, in the 1820’s, as ormolu clocks – timeless architecture keeping the well-heeled on time.

Figure 7. Portrait of painter Hubert Robert by Elisabeth-Louise Vegee – le Brun, oil on canvas, 1788. Louvre, Paris.

What is it about these, and other ancient places, that proves, for some of us, so (too?) transfixing? (There is something ironic in architects – for 37 years we‘ve practiced what Philip Johnson described as the second oldest profession – being absorbed by ruins, places we work hard to prevent the buildings we design from becoming). Interestingly, this is a question both with a long history, and without a compelling answer.

Among the greatest of the Italian ruin painters was a late 18th century French artist, Hubert Robert (1733 – 1808) (fig. 7). He moved in elite social circles; apprenticed in the studio of the most important Roman capriccio painter, Gian Paolo Panini (1691 – 1765); and was both highly charming and talented, free, it seems, of what we think of as artistic temperament. Robert befriended Denis Diderot (1713 – 1784), the famous French social provocateur; and a (very one-sided), c. 1767, imaginary conversation of theirs found its way to text: “Since”, Diderot wrote, “you (Robert) have dedicated yourself to painting ruins, do realize they have a poetry of their own, which you absolutely fail to perceive. You don’t know why ruins give so much pleasure? I will tell you the thoughts that came straightaway into my head…Everything dissolves, everything perishes, everything passes, only time goes on …What is my existence in comparison with this crumbling stone?” (fig.8)

About ruins, there are, of course, other conclusions than Diderot’s, though perhaps none so gloomily, satisfyingly Romantic. Others have remarked on the paradox of civilization’s greatest, most monumental works crumbling to dust, while we tiny, frail humans endure (for now). “The Stupendous Past”, that chapter in Macaulay’s 1953 Pleasure of Ruins, highlights another of our responses to grand places in decay – that the past was greater, so much more magnificent than the present; and that civilization inevitably moves in the direction of its own collapse.

Without denying the synthetic attractions arising from these conflicting, varying views, for us the satisfactions attending ruins comes in somewhat different ways, ways responsive to the pictures and models themselves.

Figure 8. Detail, Ruins of a Doric Temple, by Hubert Robert, oil on canvas, 1783. Hermitage, St. Petersburg.

Some of the pleasure of ruins (and their depictions) comes in what’s missing, and the invitation (and demand) that we imagine places now very different from what they once were. This isn’t simply a matter of archaeological reconstruction, though it involves this. The satisfactions come, instead, through our creative complicity in imagining the past lives of ancient places, and, now, as we survey the scenes, our presence in their history.

History is a starting point for our imaginations, rather than any kind of conclusion. Ruins set us in motion, without directing where we go; and delight comes in our minds’ predictably running off in the most interesting, unpredictable, very often delightful directions.

In Rome, this phenomenon began early on. For Petrarch (1304 – 1374), writing in the first part of the 14th century, the pleasure proved mildly hallucinatory – “…we used often to stop at the Baths of Diocletian. Sometimes we climbed on the roofs of that magnificent building, to enjoy more than in another place, wholesome air and a spacious view, silence and friendly solitude. We had under our eyes the spectacle of all these great ruins. We talked of history and of moral philosophy and of the beginnings of the arts. One day I spoke at some length of the origin of the liberal and mechanical arts. You ask me to repeat it, but without the places and the day and your rapt attention, I cannot”.

These are associative pleasures denied by the hermetic abstractions of much modern architecture. When the most majestic modern monuments – cloud-piercing skyscrapers, contortionist museums, high tech dwellings cosseting various plutocrats – finally fall to tatters, it is difficult to imagine their proving satisfying ruins, places as pleasurable and provocative as a tumbled pile of ancient Roman travertine. Las Vegas’ fully intact Forum Shops at Caesar’s Casino offers nothing of the resonant delights of the still traces of Rome’s ruined Forum, no Caesars in sight.

Figure 9. Detail, Colosseum and Arch of Constantine, by Viviano Codazzi, oil on canvas, c. 1650, Rome.

If our imaginative complicity is at the heart of the evocative delights offered up by ruins, what underlies the satisfactions of ruin paintings and models of ancient places – these evocations of evocations?

A considerable part of this appeal resides in the remarkable objects themselves. Among these now with Piraneseum are a very large, 350 year old canvas of the Colosseum and Arch of Constantine by Viviano Codazzi (1604 – 1670) (fig.9), the great, Baroque inventor of Italian architectural painting, who was called Il Vitruvio delle Prospettivo (the Vitruvius of perspective); a monumentally-scaled, 1756 view of Rome, etched by Guiseppe Vasi (1710 – 1782), Piranesi’s teacher, likely purchased in the Eternal City by the Duke of Clarendon in the course of his Grand Tour; and brought home to Chatsworth House, where it hung over the course of the last 250 years; a magnificently detailed, fire-gilded bronze replica of the façade of ancient Rouen Cathedral, featuring a clock movement crafted by renowned, then French now Swiss, firm Breguet, which our research reveals was purchased in 1835; as well as the largest, most impressive mid-19th century model of Rome’s Temple of Vespasian, carefully carved and crafted of antique marble quarried millennia ago in Tunisia – part of the stone from which the Eternal City was first assembled.

In just the same way as it is impossible to consider Rome’s history without thinking of the history of Romans, with these objects we cannot help consider the hands through which they have passed, over hundreds of years, as well as those they have yet to encounter. We think, as well, of the ways these slight souvenirs may outlive the often substantial places they represent, acting as a kind of snapshot – recording the appearance of a building as it once was, but is no more.

Figure 10. Detail, model of the Duomo, Campanile, and Baptistry, Florence, carved alabaster, ca. 1876.

Among Piraneseum’s current 19th century architectural models is an unusually large, finely-carved, replica of Florence’s Duomo, Bell Tower, and Baptistry, made of alabaster from nearby Volterra. Terrific care was taken in rendering these buildings’ details, with the exception of the Cathedral’s front façade, which appears quite plain (fig. 10). Why, we wondered, was this single part left unfinished? Research revealed that while the Duomo – among the Renaissance’s signal architectural achievements – was largely complete by 1436, the finishing of its façade was delayed for three hundred years. Its original design was thought so hopelessly out of date that it was removed in 1587, just the bare bricks remaining. The monument’s façade remained this way until an 1864 architectural competition, which led to the cathedral’s completion in 1887. Our model records the place as it was before the façade was finished, and likely dates to the early 1870’s.

As swell as these models are, and many are wonderful indeed, it is, like the ruins they so often represent, their transporting effects that are their chief attraction. Piraneseum’s paintings and other pictures act in very similar, though not identical, ways – pleasurably provoking our memories, inviting our creative complicity, a reverie really, in imagining the life of ruins and their figurative restoration. There is, however, a central difference. With ruins themselves, we are left, often delightfully, to the solitary pleasures of our own devices. With ruin paintings, we’ve an accomplice – the artist.

The painter asks not only that we see places for ourselves, through the frame of our own histories and experiences, but that we be willing to see these same places through his, often very remarkable, eyes; that we conspire with him to apprehend worlds at once familiar and, if the painter’s powers are sufficient, extraordinary, and more than occasionally, abidingly strange.

Figure 11. Detail, Capriccio with Arcade, Pietro Cappelli, oil on canvas, ca. 1725, Naples.

In his chapter “The Annals of Ruin”, in Bandits in a Landscape (1937), William Gaunt describes a group of often Neapolitan architectural painters, working “after the reaction of the seventeenth century” to the soaring, classicizing achievements of the Renaissance – (fig. 11)

He differed from the architect in having no useful purpose to serve; nor was he interested in the perfection that might once have existed. Instead he began to cherish ruin in itself and for its own sake; and just as Caravaggio and the Neapolitan figure painters were absorbed in the divergence of human beings from an ideal type, so the painter of landscape in the decay of buildings, and in all those vitiating circumstances which made them different from what they were intended to be.

The imagination this set loose did not merely copy ruins. It built them in a kind of philosophic sport. It was a lunar spirit which led to the construction of dead cities and disquieting arcades of fancy. In this strange form of creation it seemed as if ruin fed upon ruin and propagated after its own nature, filling a world of dream with spongy products of unreason.

Among the spongiest of this group was Leonardo Coccorante (1680 -1750). Spongy, also brilliantly creative, path-clearing. Art historian David Marshall writes that, in this period, Naples produced two important painters – the renowned Salvator Rosa (1615 – 1673), and Coccorante.

Figure 12. Detail, Capriccio with Sarcaphagus, Leonardo Coccorante, oil on canvas, ca. 1720, Naples.

Piraneseum is fortunate to offer several characteristic, evocative works from Coccorante’s oeuvre. As different as these are, they are united in their subject, atmosphere, and high quality. All feature imaginary ruins, set by an imaginary shoreline, eerily illuminated, in a raking yellow green light (is it a full moon?), just out of sight. In the distance, clouds billow like smoke, insisting on a sinister aspect.

Among the shadows of decrepit Classical porticos, halls, tombs, and monuments, equally shadowy figures attend to their dark business. These are scenes populated by beggars, the well-to-do, vagabonds and ruffians, bandits and their fallen prey (fig. 12).

While pursuing the identical subject matter – ancient architectural ruins – Roman painter Gian Paolo Panini (1692 – 1765), though working in much the same period as Coccorante, rendered his views entirely differently. While easily the most famous 18th century Italian ruin painter, Panini’s work is not for everyone. Gaunt, champion of the darker pleasures of the Neapolitan crowd, writes, “Panini, perhaps thought too gay in fancy, handles huge masses of masonry in a light and dextrous fashion, and introduces among them a medley of past and present figures. The warriors of ancient Rome start up amid the fallen pediments and architraves, and the peasant girl of a thousand years later looks at them with unconcern …” For others, though, Panini’s paintings – “the imagined ruins in his pictures illuminated by soft, warm daylight, architectural perspective and textures peerlessly and sumptuously rendered, architectural collapse giving rise to romantic melancholy and the orderly satisfaction of Classicism” – are the summit of this painting genre.

Among Piraneseum’s present offerings, is a highly characteristic, later canvas by this painter, picturing a variety of well-known, ancient, archetypally Roman monuments, in a highly picturesque, entirely fictional, arrangement. Near the painting’s center, per Gaunt’s critique, a ‘peasant girl’ and ‘warrior of ancient Rome’ engage an unheard dialogue.

Figure 13. The Museum as Arranged in 1813, Joseph Gandy, watercolor. Gandy was Soane’s principal architectural illustrator, and highly productive, providing evocative renderings of many of the architect’s most important works.

Between the extremes of Coccorante and Panini, dozens of others, accomplished, compelling 17th and 18th century Italian architectural painters offer their own spirited and revealing, fantastic and droll, provocative, authoritative, eccentric takes on the same theme – the ruins of ancient civilization. The sum of this multiplicity and variety of attentions? – a subject extraordinarily, almost impossibly richly rendered, nuanced and shaded, pushed and pulled; seen simultaneously from every viewpoint.

And when, inevitably, these artists’ views are stirred together with our own experiences, memories and impressions of ruins, the results may be, for us, something outside everyday experience; something instead on the order of a dream, slightly hallucinatory; like being drawn into the pictures themselves; the singular pleasures of inhabiting, just for a moment, fully formed yet fictive, delightfully, decidedly askew, beckoning, not quite benign, other worlds.

The transporting attractions of John Soane’s Museum are close kin to those offered by these pictures, putting us in mind of other places, times. There is, of course, also the Museum itself – the not-a-little-dizzying collection of models, casts, paintings, furnishings, relics, and thoroughgoing oddities fitted to the most eccentric, knowing, melancholic, and Romantic spaces ever devised – each object suffusing its neighbors in fresh, often unlikely, always architectural, associations. Evocations reflecting evocations of evocations – the Museum is a very high order architectural hall of mirrors, a not-quite-dark (though hardly fully-lit) ride, a fun house; though the hilarity is of a singularly sober sort (fig. 13).

The larger purpose of Soane’s Museum? – fashioning, in a set of very small, magnificently congested spaces, a place connected to, and putting us in mind of, the entire extent of civilization. In this, the Museum follows the path of the wunderkammer, a cabinet of wonders – settings first embraced by wealthy Renaissance collectors. Those early “cabinets’ – rooms, in fact – were places for themed assemblages of the very most astonishing and curious objects gathered from the extremities of the known world.

A late 16th century engraving pictures an Italian example given to Natural History – walls and ceiling teem with preserved fish and mollusks, niches contain seabirds, while a large crocodile is suspended, upside down from the ceiling, at the cabinet’s center (fig. 14). Later examples – kunsthammer – were devoted to the range of Art, including paintings picturing the singular and out-of-the-ordinary sculpture giving form to the fantastic. “The kunsthammer,” writes Renaissance Art historian Francisca Fioriani, “was thought as a microcosm or theater of the world, and a memory theater.”

Objects traded by Piraneseum – old ruin paintings, models, and other architectural curiosities – when assembled, form an architectural cabinet of wonders, a compact theater of some large portion of our remembered architectural world. If, in this theater, we act as director (and producer), the central pleasures come in our role as the engaged, amused, be-deviled, ultimately whisked away audience – brought to dwell, through evocative images and objects, in various magnificenses; strange, haunting, affirming and affecting atmospheres; and upright satisfactions of places fleeting, yet more than imaginary – the substantial, nearly palpable dreams that are Architecture’s chief constituent elements.

Figure 14. The oldest representation of a wunderkammer – an engraving in Ferrante Imperato’s Dell’Historia Naturele – is devoted to Natural History, with preserved fishes, stuffed mammals, and shells mounted to the ceiling and a range of built-in cabinets.