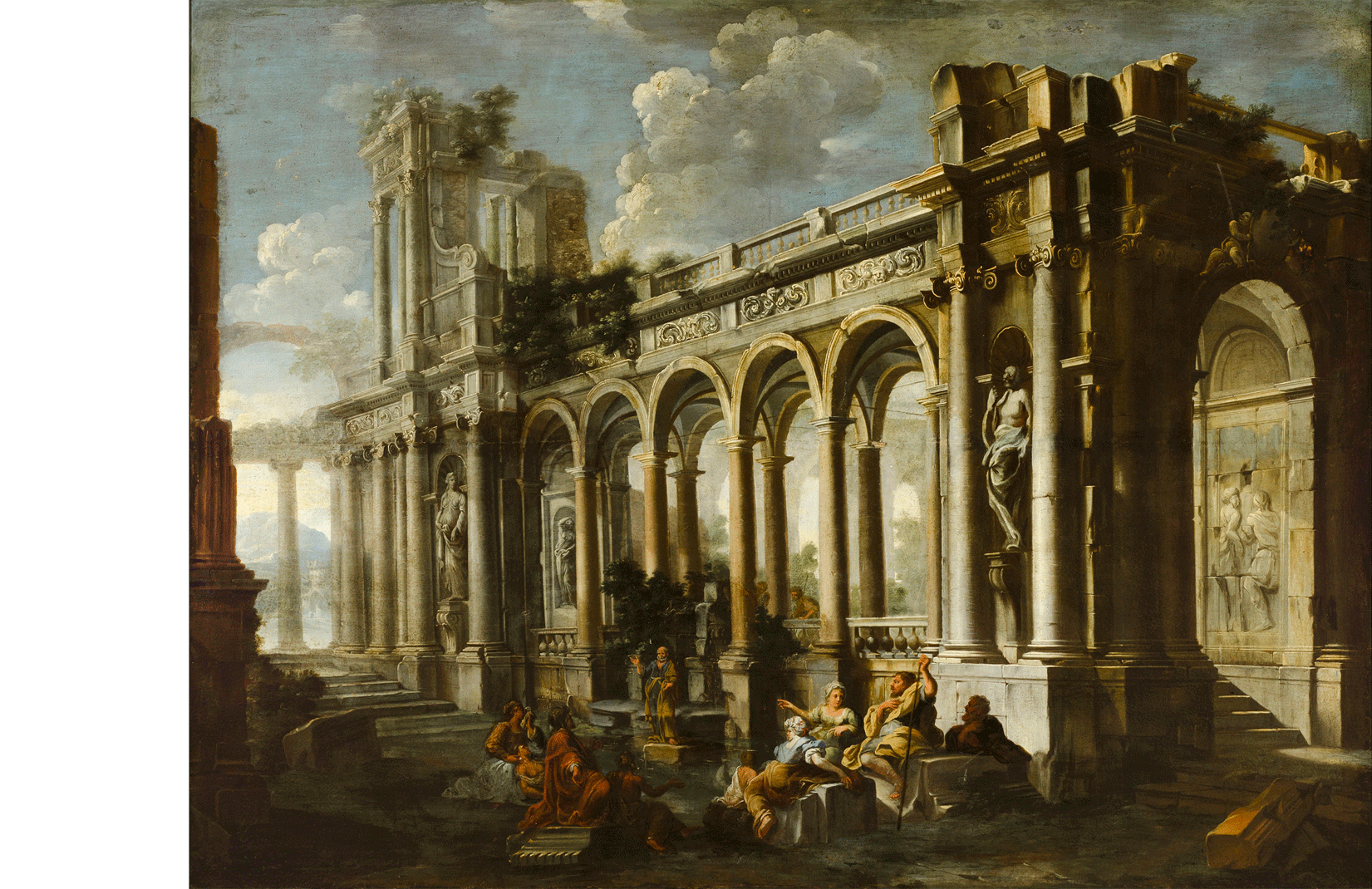

Pietro Cappelli

(naples 1646 – 1734)

capriccio with figures before a ruined arcade

130 x 172 cm., oil on canvas

- Literature

- Giancarlo Sestieri, Il Capriccio Architettonico: in Italia nel XVII e XVIII secolo, (2015), Rome, illus. Vol I, fig. 10, p. 138.

- Exhibition

- SFO Airport Museum, All Roads Lead to Rome: 17th-19th Century Souvenirs from the Collection of Piraneseum, January 24-August 13, 2017

A 1743 biographical sketch of Cappelli mentions this Neapolitan’s famously combustible and highly argumentative personality, while ceding some small portion of doubt. Says biographer Bernardo De Dominici, the painter’s words were so extreme they were eventually seen as hilarious and that those involved were reduced to laughter, just before they wanted to kill him.

Leonardo Coccorante, whose pictures we also offer, and who trained with Cappelli in master Francesco Solimena’s Naples studio, never got the joke; the two were fierce rivals. Much about Cappelli is vague or unknown. He was born in Naples c. 1700 and died there in 1724, or 1727, or 1734, depending on the account, perhaps of consumption. His father, Guiseppe, was a famous painter of theatrical scenes. A mid-19th century biographical passage describes Pietro painting architecture and perspective in oil, realistically and quickly, and with an abundance of creativity, which was widely admired. This account has him a bitter enemy of Coccorante, owing to his custom of “speaking ill of one and all.” An 1820 account has Signor Cappelli also a talented painter of marine pictures. “He possessed a fertile imagination, painted quickly and did not even sketch many of his works.“ Of the blood feud vs. Coccorante, nothing.

Very unusually, this painter also authored an architectural treatise – Sulle Regale di Architettura, On the Rules of Architecture. The various recountings of Cappelli’s life share regret over his early death. Our sorrow is different. If only architects had adhered to Cappelli’s Regale di Architettura, what a very much more interesting world we would inhabit!

Cappelli’s vision – creative, insistent, extreme, eventually humorous (just before you want to kill him) – is dexterously laid out in his architectural fantasies. These are ruin pictures like no others. Other capriccio painters portray places in the context of their surrounding landscapes. Coccorante, for example, almost always paints what appear to be vestigial ruins with views towards a harbor beyond. Panini pictures familiar ruins in the wide landscape of Rome’s Forum.

Cappelli’s ruins, on the other hand, are so extensive they crowd out the natural setting. His are architectural landscapes. Buildings and their remains run well past the edges of the frame; who knows how far. It must be asked, as well, are the places Cappelli pictures ruins at all? Unlike the tumbled down, fallen to pieces ancient Classical world forming the subjects for other capriccio painters, enough remain intact in Cappelli’s ambiguous architectural world to leave us wondering. What sorts of places are these?

This impressively-sized and scaled, highly realized capriccio is fully characteristic of Cappelli – the perspective boldly arranged, architecture crowding out the natural landscape. The subtle coloring and rendering of the long, ruined arcade (note how the columns and arches to the right, closer to the viewer, are polychrome and more highly detailed than those at the structure’s far end, rendered in grey) exaggerate its length in ways similar to those employed by Gennaro Greco, another Neapolitan architectural painter, at work in the period just prior to Cappelli.

At the picture’s center, two groups of four figures gather around a small pond, at whose center a diminutive figure – saint? apostle? – appears atop a stone block. He, in turn, gestures towards a woman laid out on her back, appearing weak and in distress. While Cappelli’s paintings often include carefully-painted narrative actors, their actions in this composition are mysterious and out of the ordinary. Owing, at least in part, to Cappelli’s early death (and, perhaps, notorious hot-headedness), relatively few works of his are known today. Professor Giancarlo Sestieri puts their number in the 30’s. The artist’s paintings are included in the collections of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, Statens Museum, Copenhagen, and Collezione M in Rome. Pictured in Giancarlo Sestiari’s 2015 Il Capriccio Architettonico: in Italia nel XVII e XVIII secolo, Rome: figure 10, p. 138, Vol I.