Giuseppe Vasi

Sicily 1710 – 1782 Rome

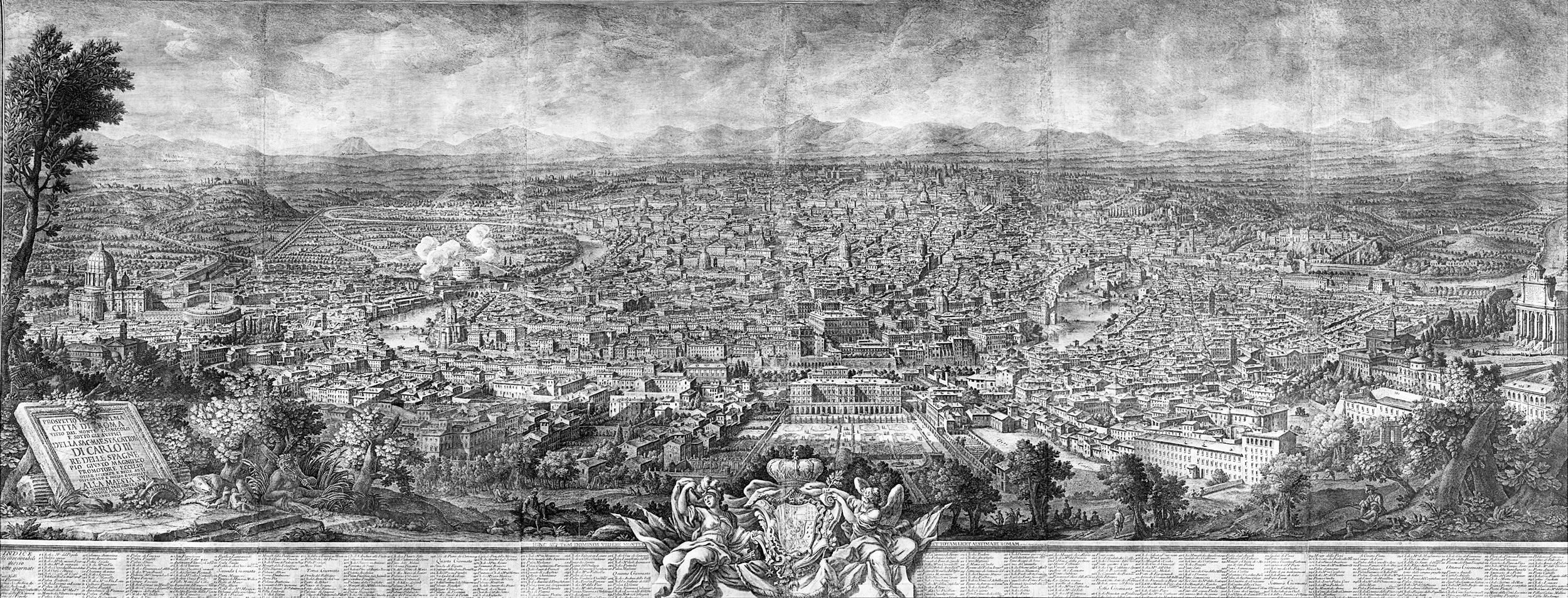

prospetto dell’alma citta di roma dal monte gianicolo

ex-chatworth house

3′-4″ x 9′-0″, 1765, etching on twelve joined sheets of laid paper

Mounted within its original 18th c. ebonized and giltwood frame

- Literature

- SFO Airport Museum, All Roads Lead to Rome, (2017), illus. pp. 54-5, and Exhibit Poster.

- Exhibition

- SFO Airport Museum, All Roads Lead to Rome: 17th-19th Century Souvenirs from the Collection of Piraneseum, January 24-August 13, 2017

In 1740, a young man walked into the workshop of Giuseppe Vasi (1710-1782), then the most eminent etcher in Rome. The self-possessed 20 year old, not a stranger to the 30 year old artist, sought work in the master’s studio, and was intent on learning something of his secrets.

The internship did not go well, the younger artist frustrated by Vasi’s withholding certain critical information, especially the best methods for handling acid during the etching process. This disappointment soon enough turned to rage, and in a studio likely awash in sharp, pointed objects – knives, etching needles, etc. – the apprentice stabbed his teacher, the motive described as murder.

Fortunately (for him and us), Vasi survived and his hot-headed charge – Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778) – seems to have gone unpunished. For the next four decades, a robust rivalry built between the two men, one decisively influencing the work of both; a competition without which Vasi’s defining work – the Prospetto dell’Alma Citta di Roma…. – might never have been achieved.

In the quarter century following that attack, Vasi’s artistic prominence with etchings of ancient Roman monuments increasingly waned, while Piranesi’s star burned ever more brightly, the younger man’s very much more dramatic, Romantic, highly-realized views, often of identical subjects (historians suggest Piranesi made off with several of Vasi’s copper printing plates) rendering his teacher’s images timid, even naïve.

In his (partial) eclipse, Vasi sought something much more magnificent than he’d previously produced, an 18th century printed blockbuster. He found the answer not in any novel methodology or shocking re-interpretation, but, simply within the history of Roman printmaking.

In 1593, Antonio Tempesta (1555-1630) published a vast view of the Eternal City – Pianta di Roma, 105 x 240 cm, printed across a dozen joined sheets. More a two-dimensional map than three-dimensional architectural perspective, it nonetheless pictured the entire city, at a size and scale encouraging examination of every street and landmark. In 1676, Giovanni Falda (1643-1678) followed suit with his own immense Nuova Pianta et Alzata della Citta di Roma, 163.5 x161 cm, also on twelve joined sheets. In 1748, Giambattista Nolli (1701-1756), an acquaintance of Vasi’s, published his monumental Pianta Grande di Roma, covering 176 x 208 cm, printed, almost of course, on twelve sheets. This especially handsome image combines an extensive plan view of the city, bordered by highly-rendered, fully-dimensional perspectives of Rome. At the top, two putti appear to be unrolling the drawing.

Vasi’s 1765 Prospetto …, 102.5 x 261.5 cm, on twelve joined sheets, is the concluding, surpassing accomplishment of this line of epochal Roman printmaking, a thoroughgoing architectural appreciation of the ancient modern city. Unlike the earlier efforts, Vasi’s view appears laid out as an immense perspective drawing, picturing the city as it then appeared from the garden of the Villa Corsini atop the hill known as the Janiculum. Buildings and other landmarks in the foreground are larger than those to the back. Unlike the earlier pianti (maps), streets are not visible, though the gaps between blocks and rows of buildings, aided by the very extensive index to the bottom of the drawings, allows locating the larger thoroughfares.

In fact, as historians have noted, in order to make the Prospetto … comprehensible, Vasi invented several adjustments to the then-existing rules of perspective, including vertically stretching the lower portion of the image.

Vasi’s radical shift in size and approach continued in this period with his four large views of Rome’s patriarchal churches, meant to be assembled with the Prospetto … into an especially impressive ensemble nearly twenty feet in length!

With this escalation, Vasi regained something of an edge on his old adversary, Piranesi, who only responded nine years later, in 1774, with publication of his Trofeo, including among other etchings, enormous images of both the Trajan and Antonine Columns – approximately 300 x 83 cm each, the pair printed on a total of twelve sheets. Piranesi died not long thereafter (1778), and Vasi four years later (1782).

For such a well-known, not impossibly scarce image, there is a good deal of disagreement concerning the dates of specific examples. At the lower left of the Prospetto, the concluding liner of the title reads “NELL’ANNO MDCCLXV,” and 1765 is agreed as the initial date of publication. Later examples sport the date ‘1829’ in the same area, the agreed date of a subsequent printing, in Milan, by Arrigoni and Bertanelli.

Less settled is the matter of where and when particular etchings were printed. This owes, in part, to the variety of formats in which these were made – there are examples composited from 18 sheets, 12 sheets, and, it appears, just 6 sheets. Too, this image has appeared on both laid and wove papers and printed with two dates – 1765 and 1829.

A recurring contention is that only the 18 sheet images date to 1765. We’ve located just two of these, one with The Getty. We’ve also located just a couple of Prospetti dated 1829. These are made up from 12 sheets, and printed on wove paper. The balance of these images – we’ve found more than a dozen – are printed on 12 sheets, on both laid and wove papers, and exhibit only the original 1765 printing date. The assertion that all 12 sheet Prospetti date to 1829 is hampered in several ways.

First, these are printed on both laid and wove papers. As with other similar etchings in this period, an image printed on laid paper is nearly always older than the precise image printed on wove paper. This is a phenomenon consistently seen in Piranesi’s etchings, among many others, and is of considerable value in helping date his prints. Additionally, with the couple of located examples of the Prospetti dated 1829, both are on wove paper.

Here, we should not forget two further examples – one from the library of George III, the other part of the Biblioteca Spendissima – recorded as printed on 6 sheets. How should these be dated?

12 sheet examples of Vasi’s great view of Rome, printed on laid paper, are by far, the most frequent to appear on today’s art market. This frequency reflects the relative numbers in which this print was originally made. Is there a compelling reason to believe these etchings date to some time other than the year appearing in their title – 1765?

What of those rare 18 sheet examples? At the same time as Vasi was preparing the Prospetto, he was also at work on four other etchings – large-scale views of Rome’s patriarchal churches. Vasi conceived these, with the large perspective of the city, to form a set of views of essentially identical heights, intended to be mounted alongside each other horizontally, forming a magnificent impression nearly 20 feet in length!

The patriarchal church views are each 100 x 69 cm, made up from three sheets joined vertically. Thus the vertical dimension of each sheet is approximately 33 cm, while this dimension of each of the 18 sheets of the rare edition of the Prospetto is 34 cm!

We wonder if Vasi, early on in the printing of his Roman panorama, realized there was no need of printing this on 18 sheets sized similarly to those of the patriarchal churches, that the Prospetto printed on 12, rather than 18 sheets, thus requiring one-third fewer impressions and correspondingly less time, forfeited none of its magnificence? Might this account for the scarcity of the 18 sheet images, which were, in fact, a type of artist’s proof?

We believe, the 12 sheets of the less scarce etching are printed in two different heights, though always in the same width. The 6 shorter plates, deployed along the bottom of the print are 34 cm tall (as mentioned above); while the 6 taller plates, directly above, are 68 cm tall – precisely twice the dimension of their shorter counterparts! This, of course, is consistent with the possibility that the upper two copper etching plates of the each vertical column of three plates of the 18 sheet variation were joined together, producing the total of 12 copper plates seen in the great majority of examples.

The Prospetto offered here once formed part of the furnishings of Chatsworth House, Derbyshire, seat of the Dukes of Devonshire and, since 1549, home to the House of Cavendish. The etching appears in two house inventories. An 1892 list shows it adorning the Audit Rooms, while an 1859 tally has it in the House Steward’s office. It seems likely that this etching was acquired by William Cavendish, 5th Duke of Devonshire, in the course of his Grand Tour in the late 1760s. Still in the handsome black painted and gilt wood frame it occupied at Chatsworth, this Prospetto from the 1765 edition is an especially richly-provenanced example of Vasi’s masterpiece.

Condition:

After its purchase, the print underwent an expert, thoroughgoing conservation.

This included demounting its twelve sheets from their deteriorated linen backing; removal of a non-original, darkened layer of varnish; making up of several losses (including two in the sky, the largest approximately 3×4”; and the face of the she-wolf to the lower left, approximately 2×2”); re-assembly of the print on thin, neutral, japan paper and remounting within the original, conserved, black painted and giltwood frame.

For safety’s sake, the original glass of the frame was replaced with Perspex. The print is set back approximately 3/8” from the rear of the Perspex glazing. The overall printed area of this Prospetto exceeds the view area of the antique frame by approximately 3/8”, all the way around, as it did originally. Because it is held back from the glazing, all portions of the print are visible.