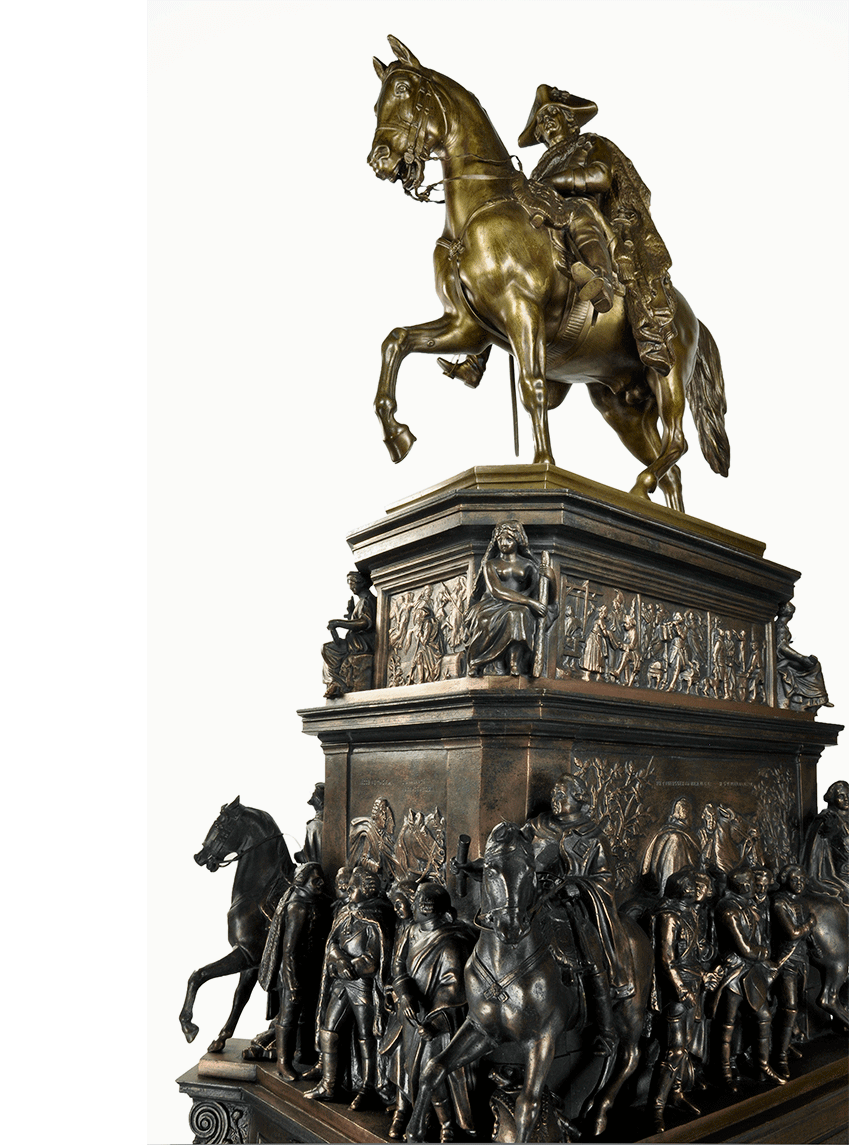

Equestrian Statue of Frederick the Great, Berlin

Reiterstandbild der Friedrichs dem Grossen, Berlin

Patinated zinc on a painted wood base

Hermann Gladenbeck, ca 1860, 32-1/2” h.

“(This) exquisitely produced model of the famous equestrian statue of Frederick the Great …. the finest and most artistic achievement.”

Illustrated Catalogues of the Paris Industrial Exhibition (1867)

There are a few 19th century architectural models which, though made in multiple, should not be counted souvenirs, not in any conventional sense.

This model records the surpassing work of the greatest 19th century German sculptor – Christian Daniel Rauch (1777 – 1857), on his most important commission and greatest triumph – the Equestrian Monument to Frederick the Great.

The monument’s prehistory, almost of course, was long and roundabout. It required 65 years after Frederick’s death (1740 – 1786) before a design was agreed upon in 1839 and another dozen years for the landmark’s bronze plates to be cast and assembled in time for the unveiling on May 31, 1851, the 111th anniversary of Frederick’s enthronement .

Rauch, the pre-eminent German sculptor of his time, had become involved in the undertaking 29 years earlier, when discussing it with the greatest German Neo-Classical architect, Karl Friedrich Shinkel (1781 – 1841).

Developing competing designs for the monument was famed German sculptor Johann Gottfried Schadow (1764 – 1850), who had been Rauch’s teacher. Upon losing this commission to his former student, Schadow exclaimed “My reputation has gone up in smoke!” Of course, he spoke not in English, but in German – “Mein Ruf est in Rauch gestiegen!” – Rauch, in German, meaning smoke.

Schadow died in 1850, a year before the Reiterstandbild was unveiled. Rauch followed in 1857, weakened, say some accounts, by three decades of work on this most ambitious monument.

Actually, the words “most ambitious” understate the purposes and presence of this 44 foot tall sculpture. In addition to the almost hyper-realistically rendered figure of Frederick atop his favorite steed, Conde – modeled on Rome’s equestrian monument to Marcus Aurelius, the base includes full-size, nearly fully dimensional figures of 74 great men of Frederick’s time: four important generals on their horses; the cardinal virtues; scenes from Frederick’s childhood; and various written tributes; all within a subtly-proportioned yet monumental framework.

If not quite the sturm and drang of an opera by Richard Wagner (1813 – 1883), another German creative at work in this general period, the Reiterstandbild’s dramatic rendition of majesty, in all its depth, leaves viewers in similar states of awe. Here Architecture is far less frozen music than royal life at a boil.

Make a model of that!

Carl Gustave Hermann Gladenbeck (1827 – 1918) had apprenticed at Germany’s Royal foundry before beginning his own business in Berlin in 1851, the year the Reiterstandbilt was completed. It may be that making this model of the monument was his first commission; he cast three in 1851. The identity of his client is not clear, though it is recorded that Rauch played a role in the design of the model. The monument’s complexity (and, presumably, Rauch’s insistence on fidelity to the monument) dictated complex innovative casting methods. What appears today as a single object is, in fact, assembled from multiple castings later joined together. A look inside the hollow base reveals the involved construction.

It should not be forgotten that Gladenbeck also produced large, outdoor monuments, including the monumental gilded bronze figure of victory atop Berlin’s Siegessaule.

The most accomplished and ambitious bronze-caster of his period, he also made very large, complex, replicas of the other key German monuments of his era – Berlin’s ca. 1900 “Denkmal des Grossen Kurfursten Friedrich Wilhelm” by the architect Andreas Schluter (1660 – 1714), and the 1871 Niederwalddenkmal, on the crest of a hill above Ruesheim, by sculptor Johannes Schilling.

Gladenbeck-made castings, in zinc rather than much more expensive bronze, were electro-plated in either copper or a bronze-colored alloy, and finished in a darkening patina. The models were cast in three sizes – the smallest half that of the middle size, which was half that of the largest size, which was five feet tall. It appears the firm continued producing complete replicas through to the late 1870’s, possibly later. A separate cast of Frederick and Conde, with the base, was also available in this later period.

The elaborate, out-size models served several purposes. Simple edification tops this list. A significant number of the large models found their ways into museums, including, of course, Berlin’s National Gallery, as well as London’s South Kensington Museum, Glasgow Art Gallery, Art Institute of Chicago, and Corcoran Gallery in Washington D.C., among others.

Other models made very swell gifts. A December 24, 1872 letter from Count Bismarck to King Wilhelm – “I thank your majesty most heartily for the handsome and distinguished present (Gladenbeck’s model) for Christmas Eve.”

The models also proved a marketing boon for Rauch, dispatched to various royals and others considering sponsoring a splendid new monument.

In our slightly more democratic world, royal blood is no longer required to possess Hermann Gladenbeck’s larger, surpassing, model of 19th century sculptor Christian Daniel Rauch’s greatest work. At Piraneseum, we accept Mastercard.