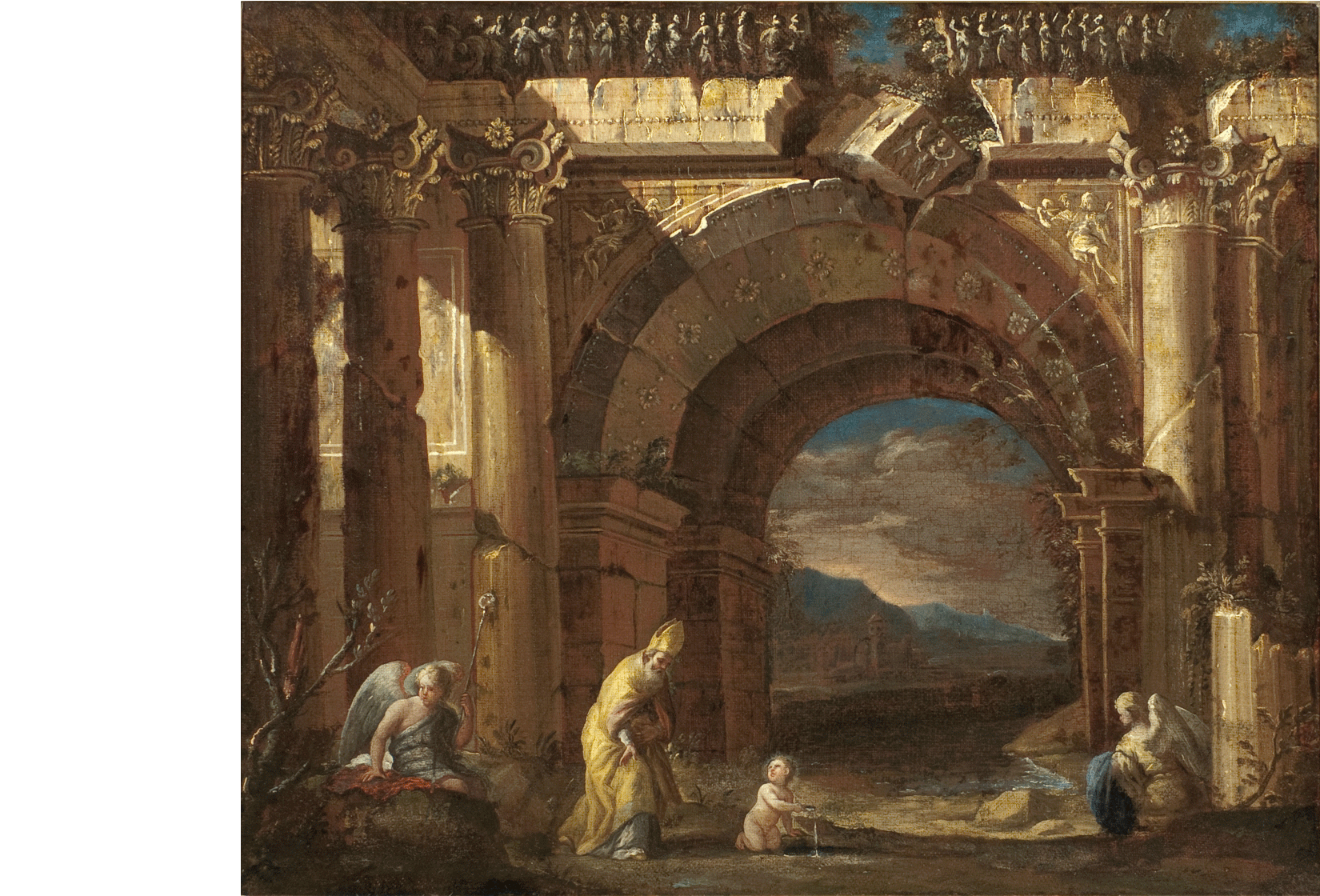

Ascanio Luciano

naples 1621 – 1706

capriccio with vision of st. augustine in ruined arcade

65 x 78 cm., oil on canvas

- Literature

- Giancarlo Sestieri, Il Capriccio Architettonico: in Italia nel XVII e XVIII secolo, (2015), Rome, illus. Vol II, figure 16, p. 315

- SFO Airport Museum, All Roads Lead to Rome, (2017), illus. p 20

- Exhibition

- SFO Airport Museum, All Roads Lead to Rome: 17th-19th Century Souvenirs from the Collection of Piraneseum, January 24-August 13, 2017

The Neapolitan Ascanio Luciano was 13 when architectural painter Viviano Codazzi came to Naples in 1634; and 26 when he left for Rome, as Marshall observes in Viviano and Niccolo Codazzi. That Ascanio (the “pseudo-Codazzi” is Marshall’s description) was Codazzi’s student is clear in the younger man’s work, which, over the past 300 years, has often been mistaken for his teacher’s.

After Codazzi’s departure, Luciano’s painting developed more individual qualities, less focused on precise architectural rendering, in the tradition of quadratura; more interested in colorful effect and, occasionally, portraying various sacred and Biblical scenes. Among these are period favorites, such as The Massacre of the Innocents and Christ Expelling the Money-changers from the Temple.

As Marshall points out, Luciano’s late works, including the painting pictured here, are signed by the artist. Ours reads “Luciano” at the lower left. This picture is very similar to AL53, shown in Viviano and Niccolo Codazzi and the Baroque Architectural Fantasy, which Marshall dates to ca.1691.

This is a lovely, colorful painting, the architecture teeming with unlikely decoration, reminiscent of the flamboyant, fantastical imagery of Francois de Nome, another Neapolitan painter of imaginary architectural views. Unlike the alarm characteristic of de Nome, though, Luciano offers his off-kilter architecture as a setting for St. Augustine’s gentle vision of a child.

While not a fan of Luciano’s late work, Marshall allows of AL53 that “it has an undeniable painterly vigor.”

Luciano’s paintings are included in the collections of the Hermitage, Prado, and Palazzo Pitti.