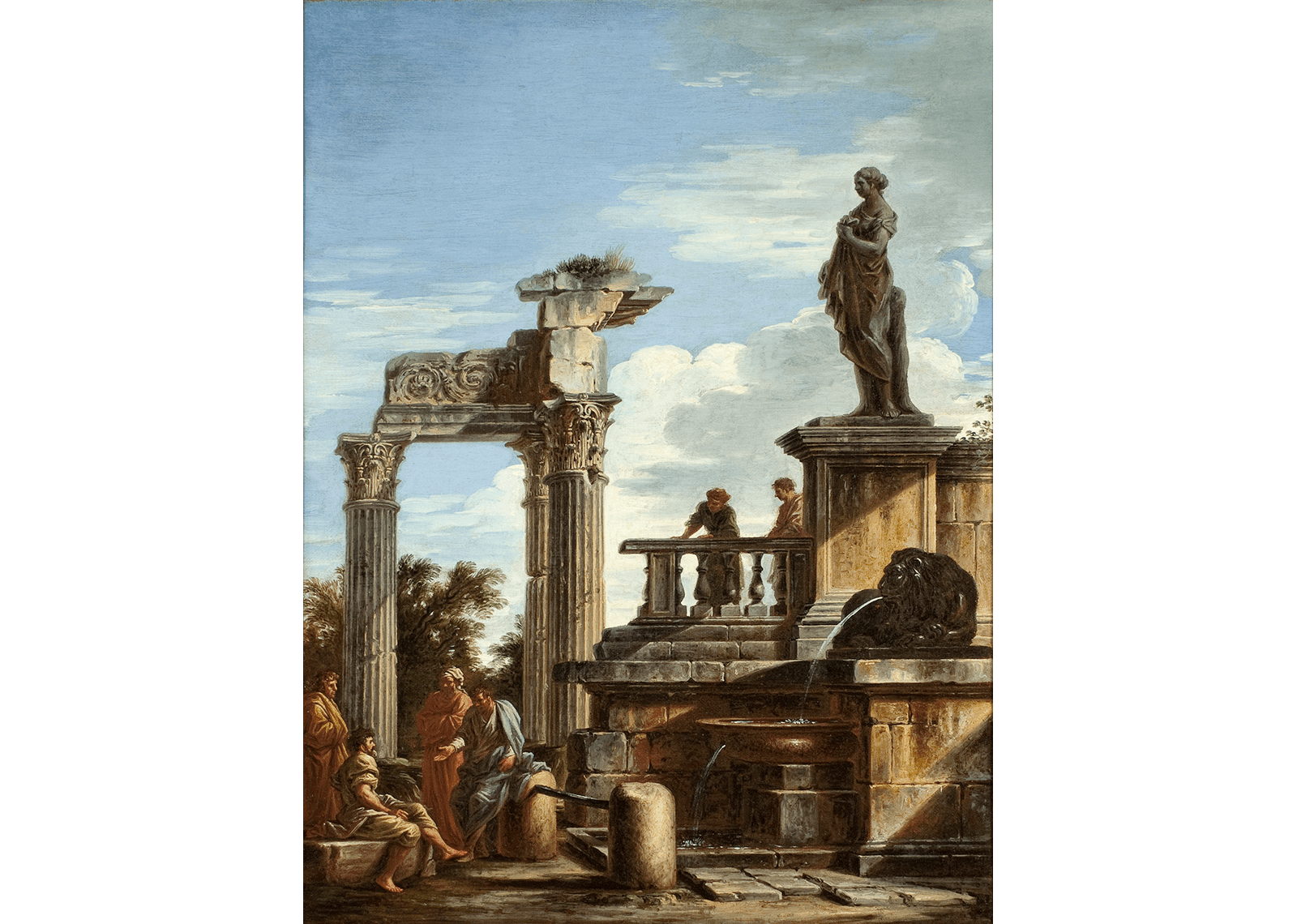

Giovanni Ghisolfi

milan 1623 – 1683

capriccio with figures among roman ruins

65 x 48.5 cm., oil on canvas

- Literature

- Giancarlo Sestieri, Il Capriccio Architettonico: in Italia nel XVII e XVIII secolo, (2015), Rome, illus. on cover and Vol II, fig. 80, p. 176.

- SFO Airport Museum, All Roads Lead to Rome, (2017), pp. 26-7, illus. p. 27. .

- Exhibition

- SFO Airport Museum, All Roads Lead to Rome: 17th-19th Century Souvenirs from the Collection of Piraneseum, January 24-August 13, 2017

With some painters, their influence on later artists and effect on the course of Art may be just as important as their own work.

Historian Rudolf Wittkower writes of Giovanni Ghisolfi, “… he made his fortune as Italy’s first painter of views with fanciful ruins.” These views – called capricci or veduti ideate – became a distinct genre in Italian painting, stretching over a century and a half. Adds Wittkower, “Rome had at least one great master (Gian Paolo Panini) who raised both the vedute esatte and vedute ideate (exact and imaginary views) to the level of great art … (O)ne cannot doubt that he received vital impulses from the precise art of Giovanni Ghisolfi, whose vedute ideate show the characteristically Roman scenic arrangements of ruins.”

Nobly born in Milan in 1623, his father an architect, and trained in architectural painting by his uncle, Antonio Volpeno, Ghisolfi travelled to Rome in 1650. There, he struck up a friendship with the Neapolitan-born Salvator Rosa, described by Wittkower as the “most unorthodox and extravagant of the Late Baroque Roman painters.” In addition to working in his studio, Ghisolfi frequently collaborated with Rosa over the course of his career, the latter adding figures to the former’s architectural views.

Andrea Busiri Vici, in his 1992 Giovanni Ghisolfi – Un Pittore Milanese di Rovine Romanae, suggests the additional influence of Francesco de Nome, a highly idiosyncratic, proto-surrealist painter of architectural fantasies, at work in Naples in the first part of the 17th century. Certainly, Ghisolfi’s “invention” of the vedute ideate – imaginary architectural scene – is easier to understand given the emphatically displacing, fantastical effects of Rosa and de Nome.

This painting, showing robed philosophers holding forth in an imaginary setting, epitomizes “the characteristically Roman scenic arrangement of ruins” described by Wittkower and is a clear precursor to later work by Panini, some of it along very similar lines. Historian Giancarlo Sestieri, writing in his definitive volume Il Capriccio Architettonico, describes this painting, -“Senza dubbio questo dipinto e uno dei capolavori in assoluto del Chisolfi” (Without doubt this painting is one of Ghisolfi’s absolute masterpieces).

Stylistically similar to No. 93 – Predica di un Apostolo Presso le Tre Colonne del Tempio di Vespasiano – in Busiri Vici’s Giovanni Ghisolfi, note especially the Temple’s similarly proportioned fluted columns, unusual composite capitals, and spiraling, floriform carving to the interior of the architrave.

Ghisolfi’s work is in the collections of the Uffizi; Pushkin Museum, Moscow; and National Museum, Prague. Cover image of Giancarlo Sestiari’s 2015 Il Capriccio Architettonico: in Italia nel XVII e XVIII secolo, Rome: also pictured in Vol II, figure 80, p. 176.